Lunar Gateway’s Framework Finalized: Technical Innovations Face Political and Budgetary Hurdles

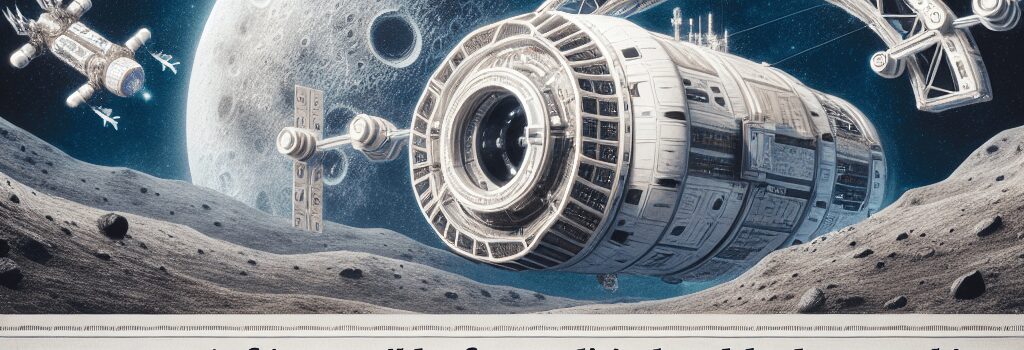

After nearly a decade of oscillating mission objectives and complex engineering challenges, NASA has announced the completion of the Lunar Gateway’s basic structural framework. Once envisioned as a platform to capture an asteroid and repurpose it near Earth, the mission’s focus has shifted dramatically over consecutive administrations. Today, the Gateway is positioned as an essential orbiting outpost supporting human exploration of the Moon and beyond.

A Brief Historical Overview: From Asteroid Retrieval to Lunar Staging

During the Obama administration, preliminary plans for a near-Earth asteroid capture set the stage for what would eventually evolve into the Lunar Gateway project. The strategy received a significant pivot during the first Trump administration when NASA retooled the original concept into a mini-space station orbiting the Moon. This station serves as a rendezvous point where astronauts in the Orion spacecraft can dock before transferring to a lunar lander, especially targeting the scientifically intriguing lunar south pole—a region believed to harbor vast reserves of water ice.

Technical Specifications and System Integration

The Gateway is engineered to expand living and operational capacities far beyond what is possible in the limited confines of the Orion crew capsule or smaller lunar landers. Two core modules lead this ambitious initiative:

- Power and Propulsion Element (PPE): Designed as the station’s central hub, PPE features 12-kilowatt Hall thrusters—the highest-powered electric propulsion system sent into space to date. These xenon-fueled thrusters, including three 12-kW and four 6-kW units manufactured by Aerojet Rocketdyne, provide high efficiency and flexibility in maneuvering heavy cargo, a feature that could eventually underpin deep-space missions headed toward Mars.

- Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO): Developed primarily by Northrop Grumman, HALO is the pressurized module that will initially support astronaut stays for up to 40 days and later expand to support up to 90 days as international contributions integrate additional capabilities, such as advanced life support and thermal management systems.

Key systems integrated into these modules include robust avionics suites, redundant command-and-control architectures, and advanced environmental control measures intended to assure safe habitation for crews operating 1,000 times further from Earth than the International Space Station.

International Collaboration: A Pillar of the Gateway Program

The Gateway not only represents a technical marvel but also a model of international partnership. NASA collaborates with several international agencies to share both technological responsibilities and financial burdens. Notable contributions include:

- Europe: The European Space Agency is developing a larger habitation module designed to extend crew stays up to 90 days, along with key refueling and communications systems.

- Japan: Building on their expertise with Orion’s service modules, Japan is tasked with developing critical elements of the communication infrastructure.

- United Arab Emirates: The UAE is contributing by designing an external airlock, a significant upgrade to facilitate complex spacewalks on the Gateway.

- Canada: Offering a state-of-the-art robotic arm, Canada plays a critical role in assembly and maintenance tasks, vital for managing multiple docked vehicles.

According to NASA’s deputy associate administrator for the Moon-to-Mars program, international partners are expected to cover about 60 percent of the program’s development costs. This cooperation mirrors the successful multinational model of the International Space Station and underscores the diplomatic importance of the Gateway in fostering global space exploration efforts.

Political and Strategic Reassessment

In recent years, the technical justification for the Gateway has come under renewed political debate. With cutting-edge lunar landing crafts like SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s lunar lander entering the arena, some stakeholders question the necessity of a mid-lunar orbital outpost. The challenges of docking a massive vehicle like Starship to a platform originally not designed to handle such loads have prompted revisions in both operational strategy and engineering. NASA’s engineers, for instance, have initiated software updates and refined control logic to mitigate potential stability issues during docking and undocking procedures.

Deep Dive: Integration, Cost, and Schedule Challenges

The Gateway program is entering a critical phase of assembly and integration. Both HALO and PPE components are advancing toward full system tests aimed at ensuring the integrated spacecraft meets rigorous operational criteria before launch. Key challenges include:

- Mass Management: With the decision to launch HALO and PPE on a single Falcon Heavy rocket, engineers are meticulously balancing the total mass and ensuring the launch vehicle’s capabilities are not exceeded. This includes iterative assessments and potential design trade-offs to achieve optimal mass distribution.

- Propulsion and Avionics Testing: The electric propulsion system is undergoing stringent acceptance testing at the Glenn Research Center, ensuring that the 12-kilowatt Hall thrusters function reliably under expected loads. Integration with onboard avionics and control systems is being refined, with experts monitoring performance metrics that mirror those of the International Space Station’s systems.

- Cost Overruns and Delays: Initially slated for an earlier deployment, the Gateway’s modules are now projected for launch toward the end of 2027, representing a five-year delay from previous schedules. The program’s cumulative costs have exceeded $3.5 billion from its inception in 2019, with further investments anticipated to reach approximately $5.3 billion. This financial pressure has fueled debate in Congress, reflecting a broader tension between ambitious exploration goals and budgetary constraints.

Prominent voices in the space policy community, including those testifying before Senate committees, have underscored the need for transparency and efficiency, particularly as NASA’s leadership faces the dual challenge of managing technological complexities and dynamic political priorities.

Expert Analysis: Balancing Technical Innovation with Policy Realities

Industry veterans such as Jon Olansen at Johnson Space Center emphasize that the Gateway program, despite its setbacks, remains a critical asset in preparing for long-duration human spaceflight. Experts point out that the deployment and testing phases not only validate advanced propulsion and environmental control systems but also provide invaluable data for future missions farther afield, such as crewed expeditions to Mars.

Furthermore, the extensive use of international partnerships injects a layer of political resilience into the program, ensuring that advancements in lunar exploration remain collaborative and multifaceted. While critics argue that direct surface infrastructure might provide a more straightforward path to sustained lunar presence, proponents affirm that the Gateway’s orbital platform is essential for iterative testing and operational flexibility.

Future Prospects: Navigating Innovation, Politics, and Deep Space Exploration

The coming years will be crucial for the Gateway as NASA and its international partners finalize integration, conduct comprehensive system testing, and refine operational protocols. This phase is marked not only by technical scrutiny but also by strategic evaluations that could redefine the balance between lunar orbit operations and surface-based infrastructure.

As NASA navigates these challenges, the success of the Gateway could significantly impact the broader Artemis program, influencing the trajectory of human exploration for decades to come. With evolving launch schedules, continuous software and hardware optimizations, and sustained international cooperation, the Lunar Gateway stands as both an engineering marvel and a litmus test for the future of multi-national space exploration.

Source: Ars Technica